Children need love – especially when they seem to deserve it the least.

And that’s when it can be so incredibly hard to find a compassionate response.

Dealing with a developing brain and a human being learning how to hooman gets overwhelming at times.

And arguing with a miniature version of myself, with the same shit-ass attitude, can get really frustrating.

When I say “Get dressed”, I don’t mean stand around watching TV with one sock on.

Some days my mom voice is so loud even the neighbours brush their teeth and get dressed.

I can’t promise to fix all my daughter’s problems, but I can make sure she never faces them alone.

Ultimately, I’m not dealing with just a tantrum, I’m training her in how to survive life and I’d like for my legacy to be the best advice she ever got.

This is but one mother’s quest to navigate the temper tantrums of a developing toddler brain because life can get hard and things can go wrong, but no matter what, you’ve got to stay strong.

When I read about the Terrible Twos, and how they “are really as bad as everyone says” and “aren’t called ‘terrible’ for nothing”, I furrowed my brow in dismay at the tempest-like hissy fits described.

Since becoming a parent, I’ve discovered that I’m reliving my own childhood parallel to and through that of my daughter’s.

Seeing my daughter go nucular for the first time (over not wanting to take a desperately needed nap), let me repeat:

It sparked a memory of experiencing that feeling myself: being filled with so much emotion that it was like an ocean trying to break out of me.

Not knowing how to dispel that feeling, I remember hysterically screaming and crying, trying to shake, beat and claw it out of myself. Not unlike what I witnessed my daughter doing.

I grew up but my emotional processing didn’t mature

When no one taught me how to handle strong emotions constructively, that initial response was frozen in time for me.

Every large emotional event that I had for years after that was defined by my inability to productively deal with my emotions.

I was plagued by toddler-like hissy fits into my late twenties, even though a lot of self-work and introspection somewhat diminished their ferocity over time.

It got to a point where the autopilot of that response would take over, in an emotionally challenging situation, and I’d have an out-of-body experience, watching the whole thing happen as if to someone else.

Seeing myself in that raging, hysterical state just made me embarrassed that I would ever behave in such a way.

To right the wrong in my own life, and to teach my daughter better than I was taught, I set out on a mission: (1) to understand why these tumultuous outbursts occur in the first place and (2) how to deal with them constructively.

What I found was that our behaviour in stressful situations (as well as what is defined as a stressful situation) is governed by our brains’ survival mechanisms.

To better understand ourselves, and our reactions, we must first understand our brains.

The reptilian brain and the amygdala

The reptilian brain is the home of our survival instincts and is responsible for dealing with life-threatening situations.

It works together with the amygdala and is activated when it perceives danger.

The amygdala triggers stress and is responsible for territorial power games.

The thing with the amygdala is that while it’s firing, there’s no point in trying to have a rational conversation with the person attached to it.

The best thing to do is to let the other person calm down first because in that mental state you’re just wasting your breath trying to have a reasonable conversation with them – it will 110% fall on deaf ears.

In order for feelings to be genuinely processed the prefrontal brain needs to be triggered.

Basically, you need to call in security to tackle the raging amygdala.

Only then can we process what just happened in a manner that fosters understanding and development.

Gregory Caremans, a psychologist specialized in the Neurocognitive and Behavioral Approach, has this to say in his Udemy course Neuroscience for Parents:

“When raising kids it’s as much about kids as it is about parents.

“In an ideal world we, the caregivers, are mature, self-controlled individuals who know what’s best for our kids and remain calm in the face of adversity.

“Yeah, right.

“In the real world, there is a zillion of things influencing our state of mind, from lack of sleep, overwork, stress to time schedules that need to be respected, and kids who don’t want to cooperate.

“So yes, there will be times that you’ll be about to lose it.

“Let me give you two little tricks that will help you remain calm when your only wish is to put your kids up for adoption.

“The first one is by activating your prefrontal brain and imagining yourself 10 years from now, looking back at this day, at this very moment.

“What will be your thoughts about this very moment 10 years from now? You’ll quickly realize that there is a 95 per cent possibility that you won’t even remember this very moment.

“And for the five remaining per cent that you will remember, you’ll probably end up laughing about it.

“So, is it really worth it to get all upset about it?

“[The] second trick is actually even easier than the first one.

“Just look at the situation and imagine how it could have been worse, and that for a matter of fact, you’re actually well off by making your brain come up with alternative scenarios to what’s currently happening.

“You’ll automatically activate that prefrontal brain of yours.

“This, in turn, will switch off the amygdala; who at this very moment has labelled your kids as a threat that needs to be dealt with.

“The prefrontal brain will re-establish balance by putting things into perspective.”

He goes on to say that our reptilian brain becomes activated even when our lives are not in danger: this is what we call stress.

Stress is a defence mechanism to perceived danger.

Now, I didn’t say ‘danger’ I, said ‘perceived danger’ because humans are probably the only species capable of worrying for something that might never happen.

Such as getting hit by a bus.

Being late with your taxes.

Or failing when you try something new.

Which all may or may not happen.

Our evolutionary stress responses

Our ancestors developed three ways of responding to a threat that we still abide by today: fight, flight and freeze.

Introverts, empaths and highly sensitive people are often acutely familiar with these.

When encountering non-life-threatening situations — your pre-schooler washing your iPad in the kitchen sink because “it was dirty” — we’re still limited to the kind of responses we’ve evolved to use when encountering life-threatening situations — accidentally stepping on the tail of a sabertooth tiger.

THE THREAT-RESPONSES EXHIBIT THEMSELVES AS FOLLOWS:

- Fight stress. A fight-response manifests itself as aggressivity, such as coming home after a hard day at work and yelling at your spouse or kids over trivial things.

- Flight stress. When we experience a flight-response, it exhibits itself as anxiety. Like feeling nervous before giving a presentation or taking an exam.

- Freeze stress. A freeze-response turns into helplessness; that’s where the expression “deer in the headlights” comes from (maybe if you keep very still the teacher’s gaze will unseeingly sweep over you and you won’t get picked to answer this question, eh?). Just thinking about having to do something that feels overwhelming will make you depressed.

The paleo-limbic brain

Where the reptilian brain is responsible for the survival of the individual, the paleo-limbic brain is responsible for the survival of the group.

Since the survival of the group is dependent on its individuals, the paleo-limbic brain defines our position within the group by regulating our self-confidence and our trust in others.

Caremans plots self-esteem and trust on an axis as follows:

Assertiveness

In the middle is assertiveness; this is when a person doesn’t have too much or too little self-confidence or trust.

A person is in balance and can say ‘yes’ to the things they want and ‘no’ to the things they don’t want.

Too much self-confidence leads to dominant behaviour.

Dominance in its mild form is manipulation and seduction.

Dominance

A dominant person can be very charming, but their kindness is not sincere since they employ dominant behaviour to get what they want.

Dominant people evaluate others in terms of how useful they are.

Submissiveness

Too little self-confidence leads to submissiveness.

A submissive person always feels that they are lucky when things go well, and blame themselves for things that go wrong.

In extreme cases, submissiveness can become melancholy depression.

Marginality

Marginality is when a person does not have enough trust in others.

Conspiracy theorists and doomsday preppers are a good example of how extreme marginality manifests itself as paranoia.

Dominance combined with marginality can result in jealousy, which can quickly sour any relationship.

Axiality

Axiality is when a person has too much trust in others.

A highly trusting person is also a very gullible person and hence the ideal target for all kinds of scams and schemes.

A very extreme form of axiality can manifest itself as mystical delirium.

Drastic shifts on the axis are always down

According to Caremans, the paleo-limbic brain is quite the archaic structure, and even though it can learn and evolve, it does so very slowly.

“Any person with a lack of self-confidence could testify: it’s not something you can solve over the weekend.

Any person claiming to be able to grow your self-esteem in record time is a fraud.”

– Gregory Caremans, Neuroscience for Parents

Trust and self-confidence take a long time to build and a sudden shift in these is always downwards, never upwards.

Usually, a significant shift towards marginality or submissiveness is caused by a traumatic event, such as being mugged or raped.

A lifetime of being bullied or not having any support while growing up will firmly lodge a person in the marginal/submissive axis and make building self-confidence and trust that much harder.

Important skills for children

Crucial skills for children to learn are those that help them recognise and deal with emotional states — both their own and other people’s.

The ability to feel and express empathy is essential.

Children gradually learn how to deal with their emotions and how to control their behaviour from their parents.

Their ability to handle their own emotions begins to develop in infancy with the support of a safe caretaker.

As parents, we act as mirrors to our children and it is with our words, tone of voice, expressions and touch that we can show our children that we understand what they’re going through, even when we ourselves are not in the same emotional state and don’t have the exact same experience as our children.

Is it easy for you to show your child compassion and empathy?

An empathic and calm reaction is important, especially when your child is in the throes of an emotional state, is a part of a fight, is testing boundaries or is bullying.

Firmness and setting boundaries are important, but the anger of an adult can thrust the child into a state where they cannot observe or understand their own, let alone anyone else’s, experience and emotional state.

When a child is panicking or is angry, we can establish this by saying “you are feeling hurt” or “this makes you angry”.

Doing so helps them to move from a state of uncertainty (not knowing what the feeling is or how to deal with it) towards a state of certainty (recognising the feeling and being able to process it).

By being calm and reacting to the situation warmly, our children see that there is really nothing wrong.

Having someone offer calm support during emotional turmoil is like hearing “it’s okay, we’ll deal with this together, you’ll be fine”, and this anchors you more firmly in the present and builds trust.

All parents are sometimes surprised by the strength of their own emotional reactions

A strong emotion can lead to a swift reaction or too quickly interpreting the child’s behaviour (and getting it wrong).

As a parent, it is beneficial to think of constructive, non-frightening ways of expressing your own challenging/strong feelings like anger, annoyance and worry.

Sometimes, it’s good to take a time-out before you begin to deal with an emotionally charged situation.

When you pause for a moment, say 10 seconds, to recognize your own thoughts and feelings, it is much easier to think of an appropriate response to the behaviour of your child.

A good rule of thumb is: all feelings are allowed but appropriately expressing them requires practice.

Good interactions foster good social skills

It’s important for the development of your child that you strive to understand both the behaviour and experience of your child.

You should find new perspectives and explanations as to why they’re behaving the way they are, and try to figure out what it is that they’re attempting to communicate with it.

Even the social skills of very young children are based on the good interactions between parent and child.

When children receive understanding and empathy in and from their own family, it teaches them how to be aware of others’ feelings.

This will help them to work more cooperatively with others in their life.

Discussing emotions and different perspectives with your child

Adults can guide small children in dealing with their emotions and in the empathic meeting of others in many ways.

Children learn to deal with their own emotions when parents and other caretakers share their emotional states with them.

It’s good to practice recognising different emotions, acts of kindness and consider other people’s perspectives in daily life with your children.

Games, stories and pictures that deal with friendship and emotions make it easy for children to recognise different emotional states.

Discussing stories and situations that you read in books, see on children’s TV programs and in different games can be helpful.

Discuss the following with your child:

- What is happening in the story/program/game?

- What was the general mood like?

- What could the children in the story have been thinking and feeling? What kind of fears and wishes did they have?

- What kind of expressions did they make?

- What did they like? Why did they like/not like it?

- What would you have done in that situation?

- How do you think the story would continue?

Why is it important to teach children how to deal with emotions?

Teaching your children how to recognize different emotional states and how to constructively deal with them is empowering them for life and setting them up for success at being themselves.

You are enabling your children to live a more balanced, emotionally stable, and mentally healthy life.

By acknowledging that our children feel bad, scared, frustrated and so on, and expressing to them that we are sorry they’re in pain, we’re paving the way for them to regain control of themselves.

As your child calms down, ask them to explain what upset them and guide them through their story.

Listen carefully and try to figure out what triggered the meltdown.

Talking may seem difficult at first, but the more your child will start to make sense of their story, the calmer they will become.

As parents, we often end up making mistakes in the moments our children are at their most vulnerable.

And that’s okay: our children need to learn that we aren’t infallible, but that we can go back to a difficult situation and talk it through.

When you relax and acknowledge your own reaction, you are demonstrating to your children how to calm down — a lesson they will apply when they find themselves in a similar situation.

Explain the events and triggers that led to you being upset and don’t be afraid to acknowledge and apologize when you’ve made a mistake.

Being more attuned to our children, understanding their developing minds, and actively seeking effective strategies to help them cope is arming them with the tools that will strengthen their resilience and allow them to pass those skills on to the future generations.

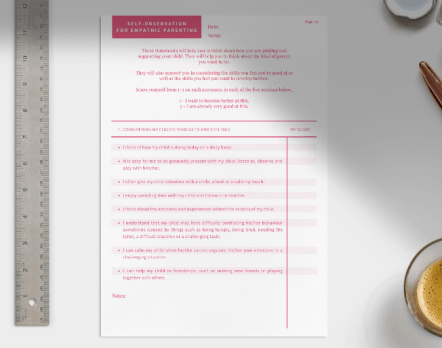

Free tool to help you develop your parenting skills

I created this assessment form, which is based on the recommendations of the Mannerheim League for Child Welfare.

You can fill it in on your computer and save it, or you can print it and fill it in by hand.

It’s a really hand tool to help you observe yourself and to figure out what your strengths as a parent are, and what things you’d like to get better at.

Filling it in takes 5-10 minutes and gives you an overview of where you are right now.

To track your progress you can save the form you fill in now, and when you fill out another one (six months or a year down the line), you’ll be able to see if you’ve made progress in the areas you wanted to.

Remember: becoming a better parent isn’t a competition and the purpose of this form is to support you in your journey as an empathic parent (not pass judgement on your parenting).

You are under no obligation to share your answers with family or friends, they are personal to you and you decide if and when you want to share.

I hope this is as useful to you as it has been to me.